COVID-19 And Future Of Public Health

Sudarshan Paudel

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic outbreak was unique in geography and extent. It suddently compelled us to make hasty preparations to protect us from its ill impacts. According to WHO, over 80 million cases and two million deaths have occurred just due to the COVID-19. Nepal itself mourned the loss of over two thousand lives leaving more than two hundred thousand ever infected. With the fast-expanding feature and tenacity of the disease, it is suspected that worse days are yet to be over

Weak Health System

The outbreak exposed the weak health systems (inadequacy of health human resources, ruined health facilities with poor technical and logistics, and weak governance and frail funding) and socio-cultural practices went awry with weak infection control measures.

The poverty (more than 18 per cent), recurrent political mayhem, poorly netted system to regularise state gears from public and private sectors impelled more chaos. Many of us lost jobs, wealth, near and dear ones, and most importantly, health.

It drew the serious attention of the government. Maximum efforts and resources were directed to cope with the situation while civil society organisations and elites were found lobbying public health as the biggest developmental agenda. People’s fundamental rights were robbed and personal traits were burgled; rural foot-trail to sky-scratched airline ways were clogged including bunged international borders with fear of disease.

The health service was tailored in new fashions and strategies of economic new normal were waved to cope with the threats which we had not noticed erstwhile. COVID-19 management key strategies; namely hand-washing (sanitizing), mask and physical (social) distancing were part of life and everyday repartee to general people.

These realities hindered an effective and immediate response to the outbreak, resulting in the disastrous public health impacts observed in Nepal. Ill-implemented COVID-19 control strategies and insufficient communication with the population led to a suspicion of ‘regular clinical care services’ that created mistrust in the health systems and their stewards. This resulted in communities’ refusal to seek care for COVID-19-related symptoms and avoidance of health facilities. The COVID-19 outbreak has also led to the disruption in service use and an accompanying substantial increase in the mortality rates of expecting mother, neonate, older people and people with chronic morbidities.

The hospital outpatient services have decreased significantly. A study reported about 80 per cent reductions in all-cause outpatient visits and cases compared with the period before COVID-19. It also resulted in fewer emergency cases at health facilities, suggesting that more cases were treated at home and consequently may not be well managed.

One of the reasons behind this is restraint in hazardous work environments and fear of nosocomial infection going to healthcare centres. On the contrary, the COVID-19 outbreak has spurred health regulation reform in Nepal and beyond, resulting in a very tenuous balance between the need to reduce COVID-19 transmission and important unintended social consequences.

WHO Recommendations

Following the WHO’s recommendations, Nepal systematically implemented exit screenings at borders and limited/banned travel for suspected COVID-19 cases. Outbreak control activities also led to the closure of schools, markets, cultural events, shrines, mass-transportation, closed borders for fear of mass transmission.

Through outbreak control activities and spurred by fears of transmission, the COVID-19 outbreak had a significant impact on the economy, slab travel business, reducing agro-forest product, curtailing social-cultural activities and trade activities.

Further public health deterioration operated through increasing poverty, food insecurity, fear of going closer to other humans (anthropophobia), anxiety, depression, lack of treatment (in case of emergencies). However, despite these negative impacts on public health and beyond, the COVID-19 outbreak has brought some opportunities that must be highlighted and sustained.

First, the devastating pace of COVID-19 led to a paradigm change in Nepal. The COVID-19 which was perceived as a ‘simple’ public health concern at the beginning, then rapidly became a threat to national security, social and political stability and economic growth.

This paradigm change witnessed aggressive public measures to mitigate its devastating impacts. For example, the government increased spending on health, recruited additional health professionals at different levels and began prioritising community participation in response to public health threats.

These efforts aim to be sustained in the post-COVID-19 phase and in addition to the existing (primarily health facility-based health human resources), public health professionals can bring significant change at the local government level.

Nepal had triggered the authority of social security functions at local government. They have mandates but lack internalizing the importance of public health professionals. The deployed health workers necessitate capacity building to meet the healthcare challenges in the post-COVID-19 era.

Second, Nepal and other developing countries have aided from multilateral, bilateral and philanthropic funding for COVID-19 control and health systems strengthening activities. Countries gradually improve the skill and competencies over the domain of emergency health catastrophic condition, extend the abilities and freights related to altruistic health services.

Besides that, promoting scientific collaboration on modern preventive and promotive methods not only in COVID-19, but nurturing good indigenous knowledge and practices. For example, the partnership for research on post-COVID-19 trial with countries of Asian and other countries as well as traditional medicinal study which assessed the efficacy of treatment in patients with COVID-19 in Nepal.

In addition to other research initiatives conducted in Nepal, there is a need for infrastructure development, capacity strengthening, ethics and scientific productivity. Owing to the COVID-19 outbreak, there is an opportunity for developing local academic training programs by health sciences academies regarding emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases having public health significance in the post-COVID-19.

Third, the COVID-19 has provided job opportunities to hundreds of young health professionals in search of their first working experience.

This has helped sharpen commitment, comprehensiveness and work culture on new health incumbents. Thus, the legacy of the COVID-19 should not only be considered from a negative perspective, and, while efforts are needed to mitigate these impacts on health programs and services, an emphasis should be put on the preparedness to face future epidemics.

Capacity Building

Preparedness regarding the capacity building efforts of public health professionals, employment results in continued population health improvements and sustained health systems strengthening. It ultimately strengthened the health system based on evidence-based public health planning and implementation and identified the resources.

In the end, the horror of COVID-19 has sparked some silver lining that could have a long-term positive impact. The lungs of the planet got fresh air, conflicting groups or people ceasefire a war-like situation (hope that will extend infinitely).

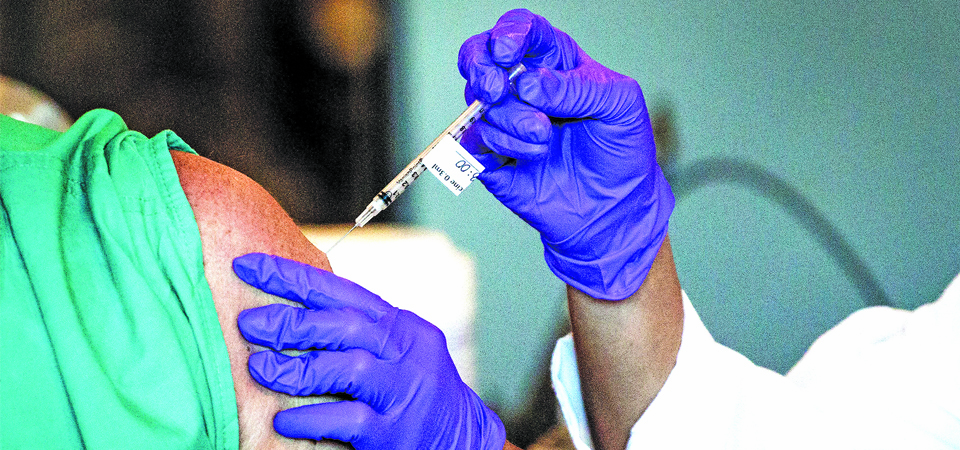

The pandemic has pushed forward the concept of ‘One Health: co-existence of environment, animal and human’. Science innovated vaccines in less than a year and thousands of other health-promoting and preventing advancements, mainly in social media, were time-honoured.

It also augmented humanitarian assistance and a sense of co-existence. One of the strong messages the government might have learnt was the importance of public health measures on health systems and multi-sectoral collaboration across all aspects of healthcare.

(The author is the faculty of School of Public Health at Patan Academy of Health Sciences)

Recent News

Do not make expressions casting dout on election: EC

14 Apr, 2022

CM Bhatta says may New Year 2079 BS inspire positive thinking

14 Apr, 2022

Three new cases, 44 recoveries in 24 hours

14 Apr, 2022

689 climbers of 84 teams so far acquire permits for climbing various peaks this spring season

14 Apr, 2022

How the rising cost of living crisis is impacting Nepal

14 Apr, 2022

US military confirms an interstellar meteor collided with Earth

14 Apr, 2022

Valneva Covid vaccine approved for use in UK

14 Apr, 2022

Chair Prachanda highlights need of unity among Maoist, Communist forces

14 Apr, 2022

Ranbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt: Bollywood toasts star couple on wedding

14 Apr, 2022

President Bhandari confers decorations (Photo Feature)

14 Apr, 2022