Memoirs Of A Die-Hard Activist

Madan Kumar Bhattarai

The book is a tell-tale reflection of a perpetual rebel who has failed to find people who can fully embrace his core values relating to various aspects. He minces no words in exposing bigwigs in various walks of Nepal’s social, political and administrative echelons.

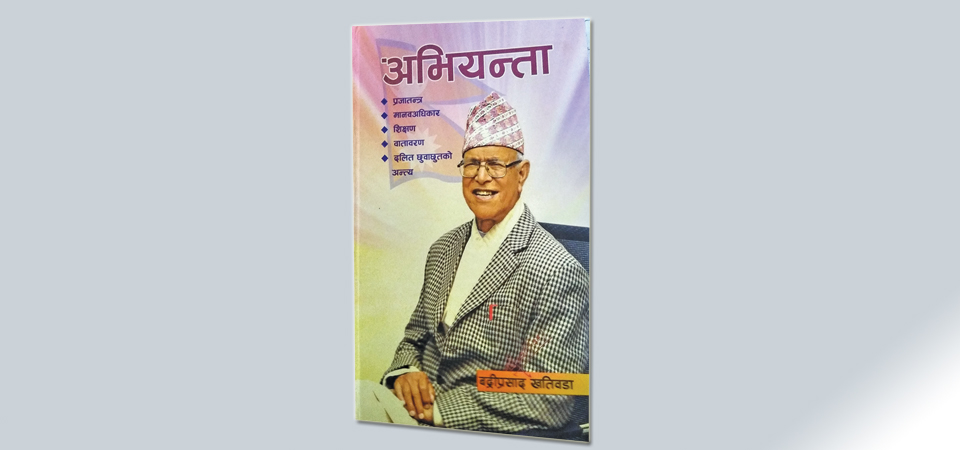

Badri Prasad Khatiwada, a name associated with many events, institutions and even distinct thought processes, has come out with a very interesting account of his own life. The work entitled ABHIYANTAA can be loosely translated as Activist, has five sub-headings, Democracy, Human Rights, Teaching, Environment and Eradication of Discrimination against Dalits (backward community) that essentially encapsulate the composite personality of the author. The book is a tell-tale reflection of a perpetual rebel who has found difficulty in finding people who can fully embrace his core values relating to various aspects and minces no words in exposing bigwigs in various walks of Nepal’s social, political and administrative echelons.

Collectively dedicated to his parents, Ekmaya Devi and Nir Nath Khatiwada and all others involved in the task of the liberation of backward community, the book is divided into 24 chapters and a photo gallery at the end. However, the main text is composed of seventeen chapters while seven chapters deal with the opinions of mostly his close relatives on Khatiwada. An author is a public man with at least three of his family members in the limelight, with son Birodh Khatiwada being a minister in the current government, daughter-in-law Munu Sigdel as a member of the provincial assembly and granddaughter Shrinkhala Khatiwada being both a former Miss Nepal and student at Harvard University.

In the prologue of the book, the author tends to draw the role of Hetauda that he hails from, in the political development of Nepal especially about King Birendra’s historic announcement of the National Referendum in 1979 to allow people to choose the system of political governance.

Initially reluctant to write any autobiography taking it as a futile exercise as he was greatly inspired by former Prime Minister Tanka Prasad Acharya, Khatiwada counts students’ movement and teachers’ movement that triggered awakening in Nepal and establishment of Human Rights Protection Front as the greatest achievements of his life. Acharya is one of Nepal’s tallest leaders with both strong common sense and tangible accomplishments with initial resistance and inhibition to share his story to his future American biographer James Fisher on the ground that his life story might not be relevant.

The second chapter deals with the childhood days of the writer as his family migrated to Makwanpur from Kalleri in Dhading district. Khatiwada has given a beautiful account of what he found and saw in and around Makwanpur with a special focus on Makwanpur Gadhi (fort) calling it as the best-organised forts of Nepal that housed the palace of Sen kings of Makwanpur before the country’s unification by King Prithvi Narayan Shah the Great. With a penchant to call a spade a spade, the author blames the post-1990 government for what he calls selling the country’s rich historical and archaeological assets amounting to 450 tonnes with the likely inclusion of many items from Makwanpur Gadhi.

The third and fourth chapters deal with educational pursuits relating to school days as Khatiwada shifted to Kathmandu and joined a three-year preparatory course for appearing at the SLC examination at Nandi Ratri Pathshala. He gives a passing reference to Nepal’s internal passport system of those days when the movement of females to and from Kathmandu Valley was strictly supervised for preventing human trafficking.

The fifth chapter deals with his association with Trichandra College as he completed B.Com. from the premier institution of Nepal. This was the period of his indoctrination into left politics as he used to be regularly tutored by a leftist intellectual Govinda Prasad Lohani who later served as a member of the National Planning Commission and Ambassador to Pakistan.

The sixth, seventh and eighth chapters deal with short stints of jobs that Khatiwada handled. First, he served under Regional Transport Organization. He then joined the Malaria eradication program, another flagship health project launched by the US government only to leave it soon to become the founding Headmaster of Bhutan Devi High School in 1959. It is paradoxical that while he was serving under two offices financed by the Americans, he had already taken membership of the Nepal Communist Party from its chairman Pushpa Lal Shrestha.

As Headmaster, he was quite a dedicated person with impressive personal experience on my part as I had joined the Bhutan Devi High School and it is to his credit that he made a very high evaluation of my intelligence to immediately admit me in Grade Nine in 1967. Khatiwada carried both school administration and underground politics at the same time even being instrumental in getting one of his colleagues at the school, Basudev Rijal, elected as Pradhan Pancha and another colleague Dor Mani Paudel was destined to become the first chief minister of number three province in recent years. Mohan Bahadur Singh, a senior bureaucrat and member of the Nepal-China border demarcation commission in 1960, was the first head of the school management committee.

Khatiwada served as a registered auditor in Kathmandu after he resigned from the post of Headmaster but was soon destined to join the school again now as an ordinary teacher and later as Headmaster for the second term. He gives credit to senior Royal Palace bureaucrat, Nepal Rashtra Bank Governor and later Ambassador Kalyan Bikram Adhikari for using his influence to boost up his financial status.

Four subsequent chapters dwell at length his imprisonments for agitational politics involved with movements of students and teachers that ultimately culminated in the announcement of King Birendra for holding National Referendum on the choice of polity, retention of then Panchayat system with timely reforms or introduction of the multiparty system.

He was instrumental in setting up Nepal Teachers’ Association as founder president. The author gives his impressions of a range of political leaders. Despite the difference in ideology and orientation, Khatiwada gives a good assessment of the Prime Minister for several terms, Surya Bahadur Thapa, but has different ratings for most of the political leaders sans Man Mohan Adhikari.

Khatiwada formally resigned from the Nepal Communist Party (UML) after the death of Madan Bhandari and joined Kuber Sharma with whom he had worked earlier and did not have good equations, and like-minded friends to constitute a new party despite the new outfit proving to be a non-starter on political terms.

The author concludes his book with a focus on positive thinking for bringing about a radical transformation in the country. I congratulate Khatiwada for bringing out such a wonderful book covering myriads of aspects of national life to the satisfaction and benefit of the readers.

(Dr. Bhattarai, a former journalist at this daily, is a former foreign secretary, ambassador and an author. kutniti@gmail.com.)

Recent News

Do not make expressions casting dout on election: EC

14 Apr, 2022

CM Bhatta says may New Year 2079 BS inspire positive thinking

14 Apr, 2022

Three new cases, 44 recoveries in 24 hours

14 Apr, 2022

689 climbers of 84 teams so far acquire permits for climbing various peaks this spring season

14 Apr, 2022

How the rising cost of living crisis is impacting Nepal

14 Apr, 2022

US military confirms an interstellar meteor collided with Earth

14 Apr, 2022

Valneva Covid vaccine approved for use in UK

14 Apr, 2022

Chair Prachanda highlights need of unity among Maoist, Communist forces

14 Apr, 2022

Ranbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt: Bollywood toasts star couple on wedding

14 Apr, 2022

President Bhandari confers decorations (Photo Feature)

14 Apr, 2022